When we fall in love we don’t decide, be it a song or a man. Yasmine Hamdan im Klangverführer-Interview

Nach fünf Jahren Victoriah’s Music auf fairaudio.de und drei Jahren Klangblog auf Klangverführer.de – in der Blogosphäre ein nachgerade biblisches Alter –, insbesondere angesichts der Tatsache, dass befreundete Blogs wie Musik am Montag reihenweise an der Erkenntnis „Musik gibt es jedenfalls mehr als genug; es ist eher die Zeit, die das knappe Gut ist“ resignieren –, ist zwar einerseits mein Jugendtraum von Musik ohne Grenzen wahr geworden – andererseits hat die schiere Musikmasse mittlerweile solche Ausmaße angenommen, dass der unbearbeitete CD-Stapel unhörbar geworden ist.

Musste ich am Anfang noch um Zusendung des gewünschten Rezensionsexemplars betteln – fairwhat? Klangwas? Kenn‘ wa nich, bemusta’n wa nich –, ist die Anzahl der (vor allem unverlangten) Zusendungen an Promo-CDs zur Freude von Deutscher Post und Benno-Regal-Produzent IKEA auf ein Vielfaches des Erwarteten gestiegen. Ein bisschen wie mit „Töpfchen koch“ und dem süßen Brei, oder „Walle walle“ und Zauberlehrling. Bei mir flutet es auch, und zwar silberne Tonträger. Man soll eben aufpassen, was man sich wünscht, es könnte wahr werden. Denn wo ich früher tatsächlich noch jedes Album, das mir ins Haus geschickt wurde, gehört habe, um zu entscheiden, ob das was für meine Leser ist oder eben auch nicht, bin ich mittlerweile gezwungen, eine Vorauswahl zu treffen, was überhaupt gehört wird. Und die geschieht, so oberflächlich das nun einmal ist, vor allem anhand des Covers.

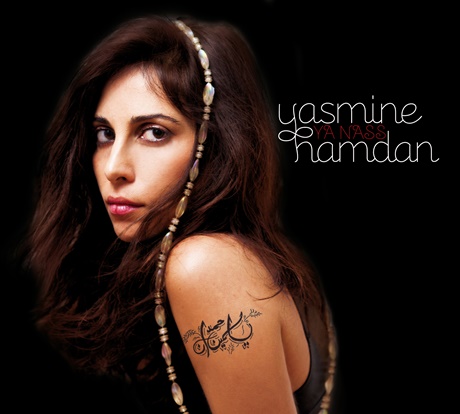

Ya Nass der libanesischen Künstlerin Yasmine Hamdan gehörte ursprünglich nicht zu dieser engeren Auswahl. Nicht nur, dass arabische Popmusik bis auf wenige Ausnahmen nicht so unbedingt meins ist – auch das Cover erinnerte mich ungut an die harmlosen R&B-Liedchen von „Perserkatze“ Jasmin Shakeri. Aus diesem Grund lehnte ich auch die Anfrage zum Hamdan-Interview erst einmal ab. Wie gut ist es dann, wenn es Promoter gibt, die für ihr Produkt wirklich brennen! Okay, es gibt auch welche, die brennen, einen überreden und dann ist die Musik schlecht – denen vertraut man dann aber auch nur genau dieses eine Mal. Uta Bretsch ist nicht so eine. Sie akzeptiere zwar meine Ablehnung, schrieb sie, doch würde ich mich hinterher sicherlich ärgern, führe einen die Stimme Yasmin Hamdans doch „direkt in eine andere Welt“. Damit hatte sie mich. Dazu kommt noch, dass ich fest daran glaube, dass man nur Dinge, die man nicht gemacht hat, bereut – und nicht solche, die man gemacht hat.

Also habe ich Ya Nass rausgekramt, reingehört – und es hat mich umgehauen! Es geht nicht einmal so sehr um die Musik, obgleich die auch sehr angenehm ist, es geht um eine Jahrhundertstimme, so speziell wie vielleicht die von Lana Del Rey oder Gemma Ray. Die Assoziation zur Perserkatze ist dann auch gar nicht so falsch, denn Yasmine Hamdan klingt wie eine faule, satte Katze, die gerade ihren Kater zum Frühstück verspeist hat, mokant grinsend und sehr sehr sehr zufrieden, dunkel, rauchig und immer einen Tick zu spät um auf den Punkt zu sein, und ein bisschen Scheiß-egal-Attitüde schwingt auch immer mit. Ya Nass ist sogar noch eine Spur lazier als die Musik ihres ehemaligen Indie-Electro-Pop Duos Soapkills, dass die französische Presse nicht grundlos als „Trip hop à l’orientale“ beschrieben hat. Kein Wunder, dass Yasmine Hamdan mich ein bisschen an Martina Topley-Bird erinnert – und auch ein bisschen an Claudia Brücken. Und ebenso wie letztere für eine ganze Generation von Männern als der Inbegriff der kühlen Diva gilt, vergleichbar höchstens einer Marlene Dietrich, wird auch Hamdan von der arabischen Welt als eine Art subkulturelle Ikone der elektronischen Musik verehrt.

Auch das nicht ohne Grund. Wofür sie mit Soapskills Duo-Partner Zeid Hamdan den Grundstein legte und was sie mit Madonna-Produzent Mirwais im Rahmen des Projektes Y.A.S. weiterverfolgte, kommt auf Ya Nass zu voller Blüte. Und die kann auch mal darin bestehen, allzu Überproduziertes über Bord zu werfen und sich wieder ganz aufs klassische Songwriting zu besinnen, alles etwas herunterzufahren und einfach relaxter angehen. Nicht ganz unbeteiligt daran ist Co-Schreiber und Produzent Marc Collin, der sonst mit dem Kult-Kollektiv Nouvelle Vague sein New Waviges (Un-)Wesen treibt. Wo Yasmine Hamdans Melodien eher einen Folk-inspirierten, zutiefst romantischen, verträumten und intimen Ansatz verfolgen, kleidet Collin sie in seine elektronischen Vibes, die vom Sound seiner gigantischen Sammlung an Vintage-Synthesizern wie dem Roland Jupiter 8 oder dem Chroma Polaris dominiert werden, dabei aber nie Hamdans Stimme und Erzählhaltung aus dem Auge verlieren. Einen tiefenentspannteren Produzent kann man sich wohl kaum wünschen. Und auch eine tiefenentspanntere Platte, die jedoch mitnichten in seichten Chill-out-Gefilden dümpelt, wird man diesen Sommer kaum hören, so ätherisch, losgelöst und vor allem un-de-chiffrierbar wie die Musik der Cocteau Twins, deren einziger Zweck nach Max Goldt die „unbedingte Erzeugung von Pracht und Eleganz“ ist, kommt Ya Nass rüber. „Es war“, erzählt Yasmine Hamdan im Interview, „wirklich sehr smooth und harmonisch im Studio“.

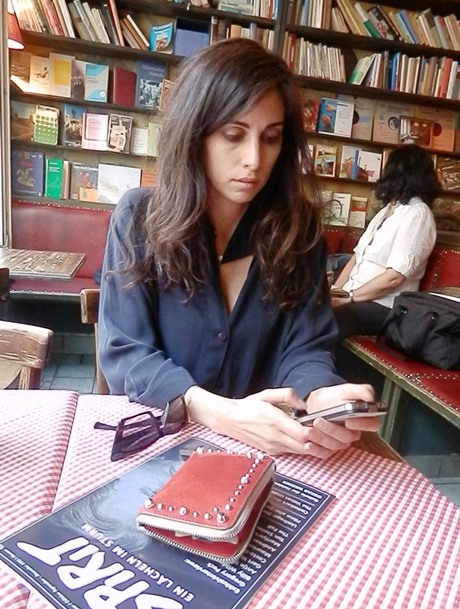

Was sie sonst noch so zu erzählen hat, wobei der Bogen von den klassischen arabischen Sängern der sogenannten Goldenen Ära über Fragen der Identitätsfindung bis hin zur Darstellung der arabischen Welt in den westlichen Medien gespannt wird, steht im folgenden Interview. Vor allem geht es aber immer um die unbedingte Liebe zu bestimmten Liedern, mit der es sich verhalte wie mit der Liebe zu einem Mann: Wer liebt, trifft keine bewusste Entscheidung, es passiert ihm einfach. Wir trafen uns Mitte April in einem atmosphärischen Café voller Bücher nahe des Berliner Ensembles, wo auch schon mal der ein oder andere nette Hund unter dem Tisch herumliegt.

Klangverführer: You have been quite successful with the Lebanese indie electro-pop band Soapkills and after that with the Paris-based electronic music duo Y.A.S. What made you start your solo career?

Yasmine Hamdan: I don’t see it like a solo career. It’s my first, let’s say, solo album – but it’s a journey. Soapkills and Y.A.S. are part of the journey, part of my getting to know more and better what I want in music, what I wanna do. So after Y.A.S., I wanted something that was more intimate, resembling more what I was; and in the voice, in the songs I wanted something more acoustic. So I started working on this idea, and then I met Marc Collin, the producer – I mean I knew him before, but then I went to see him with some demos, and we started to work very … very step by step. I like to work on drafts, like … I have the melody, but I don’t always have the final lyrics when I start recording. I have some structure, but I like to keep it open, because when we are in the studio – anything can happen. So this is how we started working on this album.

You’ve just mentioned Marc Collin of Nouvelle Vague who has co-written and produced your new album Ya Nass. How did this cooperation actually come into existence?

Well, I met him in maybe 2005 or 2004 when he was working on the Nouvelle Vague project and I was starting to work with Mirwais, so we didn’t really … We tried some stuff in the studio but we said we’d postpone it. And four years ago – five years later – I came back. We were still in touch, we had dinners and we went to parties together, but not always meeting. And when I knew exactly what I wanted, I went to him – and he was perfect, because we had so much fun in the studio and he’s a very inspiring person because he trusted my intuitions and he trusted me. So we never really had conflicts when we started working. It was really smooth and harmonic.

Did you already live in Paris at that time?

Yes. I started to be on and off in Paris … I think in 2002. I left Beirut in 2002. I wanted to come to a bigger city, meet musicians and enlarge my world, and because I did this degree in psychology I wanted to pursue my studies – which I didn’t. But in the beginning I came as a student. I started to study psychology in Beirut, and parallely I had my musical career going on. And … you know, I was born in the middle of civil war. So through all my childhood I was living between many different countries and cities, like Beirut, Abu-Dhabi or Kuwait. And then my family and I came back to Beirut in the Nineties because of the end of civil war, and I stayed in Beirut from the Nineties to 2002. Then I moved to Paris.

And you still live there …

Yes, but I travel a lot and I go back to Lebanon a lot. I can say that I don’t see a lot from Paris and I can also say that my apartment is my country, because I spend a lot of time in solitude or with my boyfriend – I spend a lot of time in my space.

Let’s talk about your new album. On your self-titled solo debut from last year you were using folk songs from Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, and Kuwait. Now on Ya Nass, the melodies and lyrics are inspired by the attitude of the classical Arab songstresses from the so-called “Golden Age”, and in addition, there are some interpretations of rare old songs, like In Kani Fouadi that was originally recorded by Egypt singer and actress Leila Mourad …

Well, it’s not exactly that. When I start working … I nourish myself before. I need to get in touch with a lot of things that inspire me. So I collect a lot of old music and I listen to a lot of music. And when I started to work on this album, I knew that I wanted to do some cover songs because I fell in love with these songs – it’s like I have crushes on a song and I feel like it was written for me! And I take all the freedom to re-appropriate the song. So I knew exactly that there were some songs that I wanted to sing though it’s sometimes challenging for the voice. The melodies in these songs can be extremely sophisticated – and it’s also challenging for me to take them somewhere else. And also sometimes it’s challenging for me to bring them from a past when they had something like a social or a political layer. So I knew that I wanted to sing some of these cover songs– but completely transformed. Sometimes my version has nothing to do with the original. But these artists, they are my …

Heroes?

No! Rather my big … my inspiration, my love. You know, I fall in love with artists, I get obsessed with them, I live with them. And they live with me – in my house (laughs). So I have this part on the album. The other part is my compositions. Here it’s different. I have to get in touch with myself in order to write the lyrics or to find the right words or to find the right ways to the words and to find the right meaning to articulate the self. So for me, melodies are very easy. I can grab them easily. But the lyrics are more difficult to find. It’s another part of the work, so I really have to write the songs and know why I’m writing them and therefore get in connection with my desires and myself. In this moment I have to try to be sincere and coherent of what I want. So I try to make a balance within the album between some of the cover songs that are inspirations from the past and some of the new ones. In my melodies, there are things that are more pop, or more … for example, a song like Samar is more Indian …

Yeah, it really sounds a bit Bollywood!

… and Deny for example is something … I wanted something really grave and a little bluesy.

It indeed sounds a bit like Southern Jazz – to be honest, it’s my favorite track on the album!

Oh, thank you!

When you put the CD into the player and hear those guitars and your rich throaty voice, you really start to believe that you’re listening to a Cassandra Wilson album – despite the Arabic lyrics!

Thank you. You know, what I feel I’m lucky with is that I can understand and speak many dialects because I lived in the Gulf so I have access to the Gulf music, to the Iraqui, Kuwaiti dialect and it’s different! I also have access to the Palestinian dialect – I live with a Palestinian guy –, the Lebanese, the Egyptian … I live with a lot of old Egyptian music … And you can feel the difference without knowing Egyptian, because some words sound different in the different dialects, and even the fluidity or the rhythm in the lyrics is different because I change the dialect. I’m very lucky to have so many choices. And because I have desires to try many different things, there is something very exciting about the idea that it’s a very raw material.

You have just explained that you were trying to find a balance between your own compositions and these kind of cover songs of the old Arab tunes …

Well, you wanna know how I do that?

No, I’m just wondering … in the context of these old songs …What’s the story of your fascination with the veteran sounds?

Well, you know, when I started with Soapkills, I was singing in English, in the beginning. And I struggled about what I wanted to be, the choices I wanted to make and the life I wanted to have. You know, I was in Beirut, end of the Nineties, end of civil war … It was a very special moment at this time because you lived in a city where half of it was destroyed and you don’t know why. And you are from a generation that’s having ruptures. I didn’t have a clear answer to what was my identity, where I came from, because I have lived in many places and I didn’t feel really that I was at home. So, at some point, all of this made me … got me a passion. Through this music, through discovering these artists, I started to discover people that I would identify to, culturally and artistically. So I started to research these people and I started to find my own leaders and to feel how I could create my own narratives and my space. This was where my … let’s say: desire … went. It came to me naturally. I started to listen to the first woman which was Asmahan, and Asmahan has incredibly beautiful songs and an incredibly beautiful voice – and she also has very edgy songs, because she was a … very edgy woman! You can feel that in the songs she is performing. And from her I went on to others and others and others, so I started to have this big collection of old Arabic music. It really came naturally, I don’t know why!

Like … as a kind of spiritual home, maybe?

Yes. And also in the sense of a teaching context. I’m an autodidact. I never really learned music. I mean, I did – I spent three years in conservatory. But I could never be rational with it. So for me, these people initiated me. And part of the initiation or part of my experimentation or of my learning music was to go and find. For example, I would find myself in Damascus and go to a place where I knew they had old music and I would buy many cassettes and then I would come back home and listen, and then one of the musicians would give me something or open my eye or give me a desire, a desire to do things, and this is part of the whole process of initiation. Maybe … I think it’s a spiritual thing but I come out of it with something. You know, in my tradition, music was always oral music. It was not written music. It’s only started to be written in I think 1932 or somewhere in the Thirties, this was when through the Conference in Cairo the Arabs adapted to the international language of music. So we come from an oral culture. And some of the songs I sing – I never heard them on record. It was my grandmother who used to sing them for me. So I come from a place where music is a very … organic material.

In the sense of that it constantly changes and everybody adds something to it?

Sometimes, yes. And also I think it’s alive.

Is keeping the old songs alive something you are aiming at?

It’s not a strategy. It’s normal. It’s part of my desire to bring these people alive – for me, they are alive!

So you’re not pursuing any educational intentions …

No. Like I said before, it’s not a strategy. It only comes from … hope. You know, these people gave me hope. Sometimes I feel like a passeur … a passeur de cultures. And I think all artists are like that. Actually, every human being is like that – I mean, you’re like that to your children, you are like that to your family, you are like that to your world, and it’s a normal thing. It’s life!

You just mentioned that in the beginning you were singing in English. I have just come across another interview with you where you are quoted to have said, singing in Arabic later for you has been “a statement“ …

Well, I don’t know if I used the word „statement“. But let’s say, for me, I have been searching for something and I found it when I used the Arabic language. Like, I was a bit confused about my identity, having lived in so many places and not really feeling anywhere at home. And singing in Arabic was also very taboo when we started Soapkills because it was not cool. And also, there was no underground scene. So we were one of the first bands to do anything that was not socialized with what was happening. For example when I started to sing in small bars and other very little places, it was not very common to have performance places. And singing in Arabic for me was very important because it’s a statement by itself, but I didn’t do it for that. I could sing in English, I could sing in any language … but for me it was where my feeling, where my being was. That’s why I started to sing in Arabic. Because it felt right.

So it was kind of a personal decision because it gave you the freedom to express yourself just how you were and find your identity and not because you wanted to change the image of how the Arabic world is portrayed into something more positive?

It’s not this or that. It’s both. On the one hand: It didn’t exist and I felt so thrilled by the idea of being part of something that would change, that would initiate changes. And also, because I fell in love with Arabic music and it allowed me to express my emotions the light way. And when we fall in love we don’t decide. So this was like falling in love with a man. And also, because for me it was like an evidence. An evidence that I should sing in Arabic because this is where my voice is and this is where I come from and where my roots come from. And there’s something about it that has also a political meaning in the sense that it’s possible to propose, that there can be alternatives, open spaces of dialogue. So singing in Arabic is also like if you want to fight for something, if you feel this is the right fight. And of course it’s about what you have said about media and portraying Arabic culture. We are living in difficult times that can be very annoying – for both sides. When I watch the news and see how Arabs are portrayed, it can be very annoying. And sometimes it’s also very annoying how Arabs respond to this and how they argue. So I don’t feel comfortable with each … you see, I don’t think it’s this or that. In the Arabic world we’re living in changing times, things are going to progress and there are still many fights to be fought. And even I fight with myself to find the best way to be free. And this is a fight you’re having in yourself. It’s not about the outside world, it’s about yourself and what you think is right or wrong. It’s important that I come from a part of the world where changes are happening. In the Arab countries I think that a lot of artists think that now we are responsible … we have a voice and so we are responsible for what will happen. I think all artists feel that but of course I’m speaking only for myself.

Talking about identity … Your album contains a song called Beirut …

Yes, Beirut is a song that contains the lyrics of Lebanese lyricist Omar el Zenni. Although he wrote them in the 40ies, for me it felt like it was about my story with Beirut. It’s very modern; one could think it’s talking about today. It mirrors a lot of how Beirut is today – but above all it says a lot about my relationship to Beirut. For me, it’s a love-and-hate affair. I’m more detached now. But it’s a very beautiful place, a very inspiring place – but it’s also an annoying place where lots of things I’m not okay with happened or are still happening, like for example a lot of corruption, things that I just don’t synchronize with and that create this love-and-hate thing. But a very beautiful thing about Beirut is that you can find these places where you can have a very special time, very special moments with very charming people. Another reason, or let’s say: one of the desires why I had to sing this song, too, was because it has a lot of emotional layers. It means a lot of different things to me.

Being a non-Arabic speaker, for me of course it’s almost impossible to reproduce these meanings. Let’s talk about that language barrier. I think the majority of your western audience doesn’t understand your lyrics. How do you compensate for this?

Well, I don’t think I need. Do you feel something?

I do for sure – but without the liner notes I don’t know what you are singing about.

Do you need to know?

That’s an interesting question. For me, your music, your record works. But would it work for everybody else?

I’m not sure. But let’s go to the rough. For example, if you take the Cocteau Twins … They sing in English but sometimes you get the feeling they would sing in their own language. And nobody’s asking or questioning. For me, it’s rather the emotion that is the most important thing. I never thought that Arabic language or language at all is a barrier. It’s not a ghetto. I fall in love with singers singing in Chinese or Pakistani or Indian … and even when I listen to English pop music or even German music that I listen to sometimes … I might not really have access to the meaning but I have access to the organic or to the vital … to the living thing that creates an emotion. So I rely on that a lot. When you can open your heart and create magic or be in the moment, you can find ways to communicate and people will receive your communication. It’s like a bottle you send in the Sea – somebody maybe will find it.

Because music is a universal language?

I think so! And you know, I think that Arabic people that listen to my music – they get the music in a different way. And the ones that don’t understand it – they get it in another way. And it’s okay. It’s different – but it’s okay with me. And it’s also for very different reasons that I love the songs I listen to. Some songs give me joy. Some have this melancholic aspect that I’m hooked on etcetera. It’s only accepting the complexity of the world we are living in.

I know you gotta hurry because tonight you are invited by indie duo CocoRosie to the Berliner Ensemble where Robert Wilsons Peter Pan that features CocoRosies music is on. Apart from the friendship – do you have any musical connection to the Casady sisters?

I’m not sure if I want to answer this because I don’t want it to sound … I don’t want to sound using because they are my friends and inspire me. And when a fried or a person is inspiring to you … you know, it can even be your grandmother who gives you change, who gives you hope, who gives you love … Maybe not everybody will function this way but for the way I live my life I constructed a parallel world I live in. A reality that is very linked to my emotions, my desires and the things I need, the people I need and the things that I especially identify to, where I feel inspired and happy. And so I try to be around people that are inspiring me all the time. In their work, in the way they are, in the cooking, in the reading, in the writing. So, these girls have been very inspiring to me and I love them.

Ya Nass ist am 31. Mai 2013 bei Crammed Discs erschienen. Eine Rezension können Sie in der aktuellen Ausgabe von Victoriah’s Music auf fairaudio.de lesen.